Every day, colonies of ravenous microorganisms—dwelling within the dense root systems of hydroponically grown plants—help clean and repurpose nearly 400,000 gallons of campus wastewater for non-potable uses. These colonies are just one of the complex biological processes that make up Emory’s cutting-edge WaterHub.

Five years ago, the WaterHub became the first facility of its kind in the U.S. to harness the power of nature to recycle water for heating laboratories, cooling classrooms and flushing toilets in residence halls.

Today, it provides for nearly 40 percent of Emory’s total campus water needs, says Ciannat Howett, Emory’s associate vice president for resilience, sustainability and economic inclusion. “It’s also modeling a more resilient and sustainable alternative to traditional sewage treatment,” Howett says.

More than 300 million gallons of wastewater have been processed at the WaterHub since April 2015.

HOW THE WATERHUB WORKS

Developed through a private-academic partnership with eco-engineering firm Sustainable Water, Emory’s WaterHub was constructed on a modest campus footprint, operating within two facilities situated off Peavine Creek Drive. On one side of the road resides what looks like a lush, plant-filled greenhouse, while across the street sit concrete processing tanks that, to the naked eye, appear to be large, ornamental planting beds.

Bananas growing in the WaterHub greenhouse.

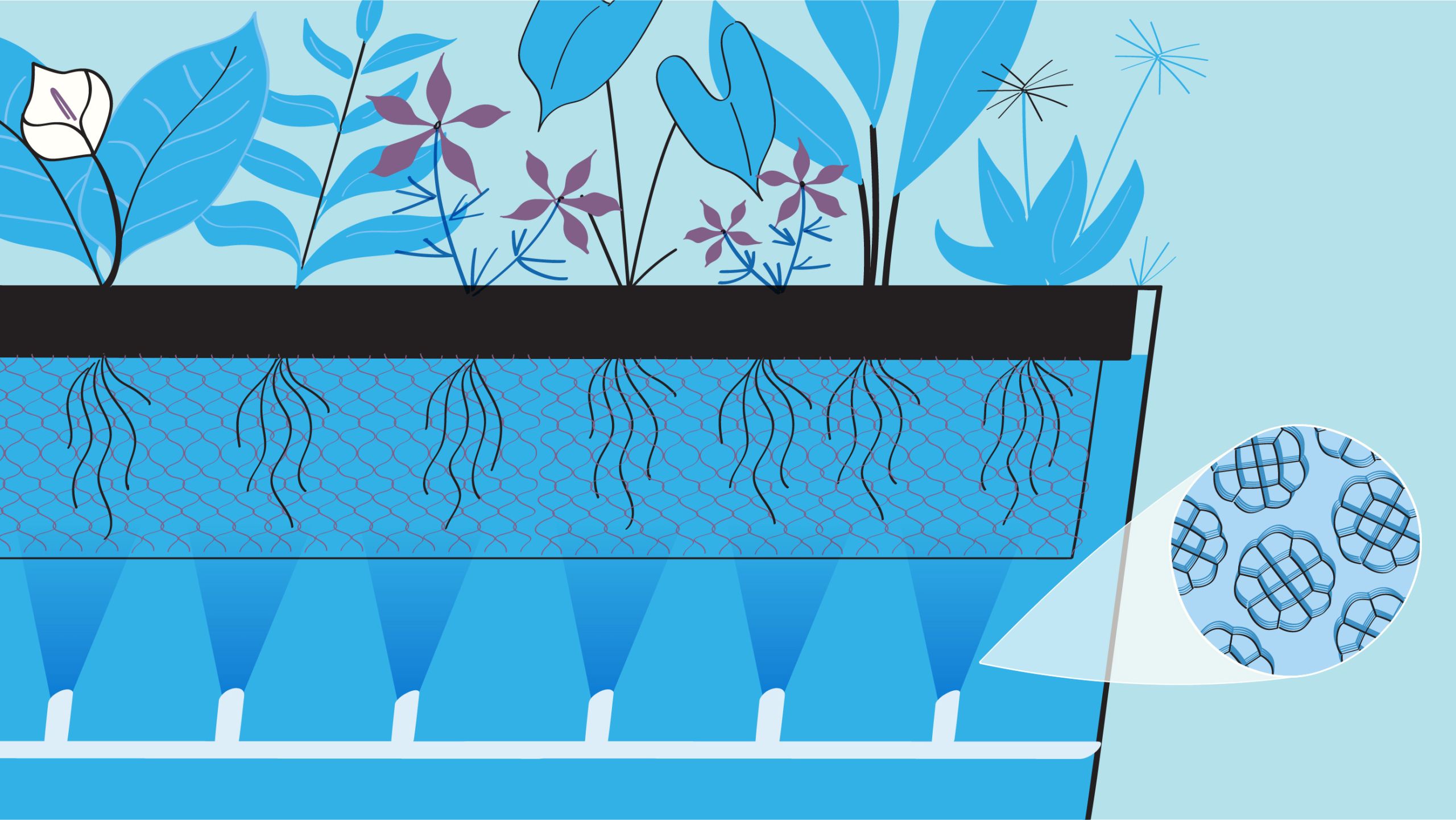

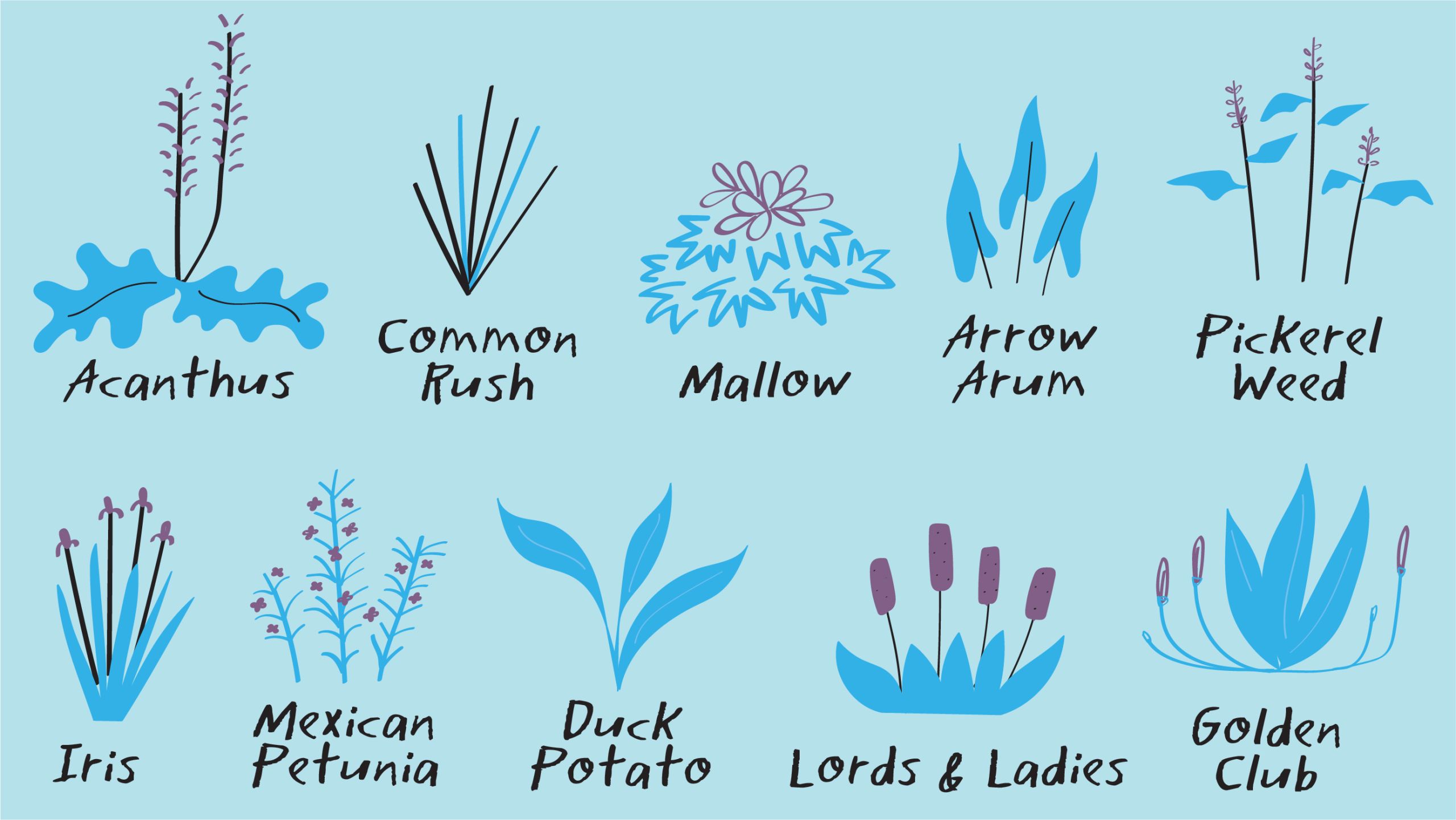

Together, they house a flourishing ecosystem—a dense web of real and synthetic plant roots that support critical microbial habitat for millions of naturally occurring microorganisms that digest the organic matter in campus wastewater.

Plant roots provide thriving habitats for microorganisms and beneficial bacteria.

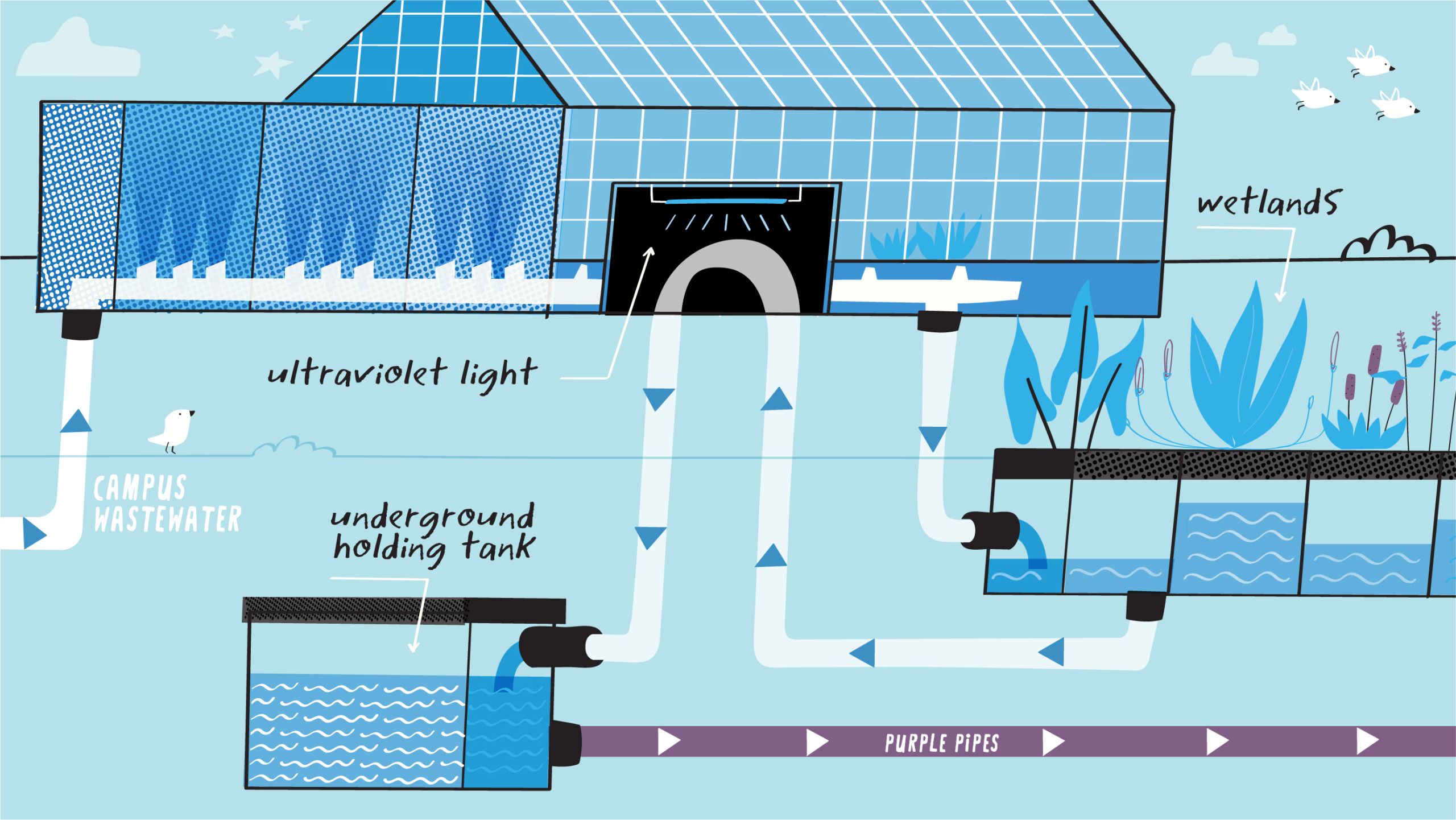

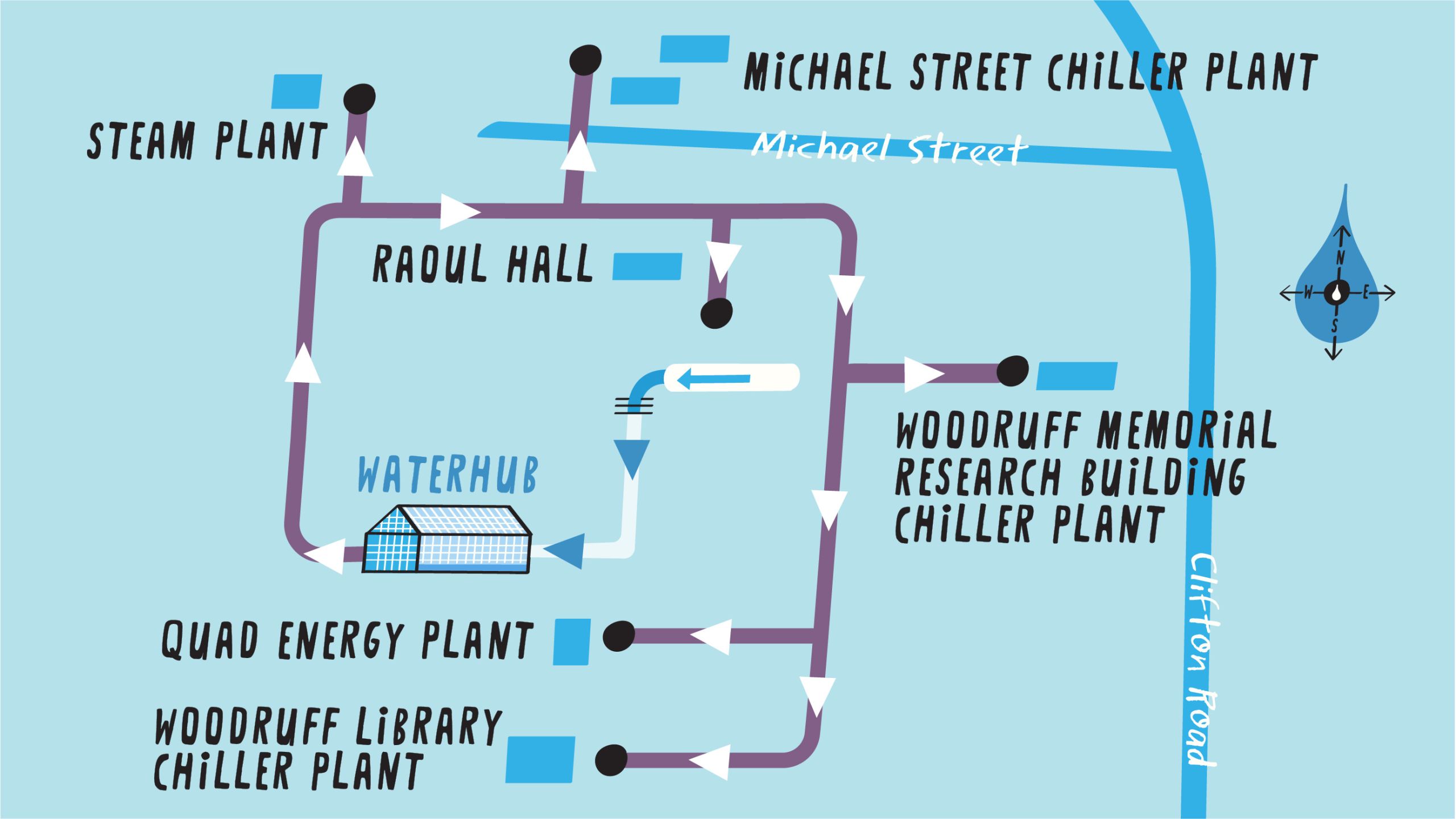

Once water flows through a series of natural earth and plant bioreactors at both sites, it returns to the greenhouse for ultraviolet light sterilization and chlorination. Recycled water is distributed back to campus via a 4,400-linear-foot long network of distinctive purple pipes, destined for steam and chiller plants—which heat and cool over 70 buildings—and for toilet flushing in select residence halls, where the reclaimed water is tinted a subtle blue hue.

Horsetail is one of many plants that help break down waste and pollutants.

All told, the treatment cycle—which is quiet and odorless—takes about 12 to 18 hours.

The system also offers a safety net: In the event of regional water disruptions, a 50,000-gallon underground emergency clean water reserve remains available for campus heating and cooling.

FOLLOW THE FLOW (STEP BY STEP)

Here’s a seven-step process that shows how sewage water enters the WaterHub and comes out clean enough to be used in Emory’s steam plant and three campus chiller plants, as well as select residence hall toilets:

STEP 1 – First, the WaterHub collects wastewater from sites around campus.

STEP 2 – At the greenhouse facility, the water is then pumped through bioreactors that introduce colonies of microbes and then through hydroponic bio-habitats.

STEP 3 – Microorganisms consume nutrients, converting blackwater (from toilets) and graywater (from sinks, showers, dishwashers, etc.) into high-quality reclaimed water.

STEP 4 – Some of this water (about 2,500 gallons daily) is next pumped to a nearby reciprocating wetland, which mirrors the ebb and flow of tidal marshes—home to more waste-eating microorganisms.

STEP 5 – A small amount of solid matter is recycled into the sewer system.

STEP 6 – Recycled water is clarified, filtered, and disinfected by ultraviolet light.

STEP 7 – It’s then distributed through special purple pipes to campus steam and chiller plants, as well as to some buildings for toilet flushing. The entire treatment process takes 12 to 18 hours.

A RESOURCE FOR STUDY AND RESEARCH

“What’s really innovative is this smaller footprint, the idea of decentralized treatment and reuse that is taking place right on this campus—I think it’s our future.””

—Christine Moe, Eugene J. Gangarosa Professor of Safe Water and Sanitation in the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH) and director of the Center for Global Safe Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene at Emory

“When I take my classes to see this facility, that’s what I tell them,” Moe says. “‘This is our future. It will be a model,’” she adds. “And when visitors to our Center tour the WaterHub, they get excited, because they see the potential for other parts of the world.”

Moe has long utilized the WaterHub as a living laboratory for Emory students, who were monitoring the microbiology of wastewater samples even as the facility was preparing to launch back in 2015. In her course “Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries,” students collect and analyze wastewater samples before and after the WaterHub treatment process over a five-week period — data that is shared with the WaterHub facilities team — and examine the reduction in bacteria that indicate process efficacy.

Not only does the facility open their eyes to pressing issues, for a generation facing significant environmental challenges, the WaterHub offers a rare success story. “In class, we talk about water scarcity, which will be one of the defining issues of their future,” Moe says. “It’s nice to also be able to talk about solutions; it’s important to set that example.”

A GLOBAL MODEL FOR RECYCLING H20

Since its installation, the WaterHub has drawn international interest from schools and universities, corporations and municipalities. And it’s won 16 national awards so far, recognizing the project for achievements in innovation, sustainability, environmental performance, construction, engineering and land use.

And as Moe predicted, it appears that the WaterHub has become a model for other institutions. One week the facility may host visitors from Apple studying it in preparation for the construction of their new corporate campus in Austin, Texas; another week executives with the non-profit Livable Buckhead tour it interested in how they can apply it to “future-proofing” properties for an era of water shortages.

Christine Moe helps test water cleanliness at Emory’s WaterHub.

In fact, Duke University officials have acknowledged plans to construct their own version of the WaterHub, projected to open next year.

“In terms of overall performance, it’s exceeded all expectations,” says Bob Salvatelli, director of business development for Sustainable Water. “As a model home, it’s been a watershed project. We bring clients there all the time—it’s an incredible showcase.”

With the challenges of climate change, Salvatelli anticipates interest in WaterHub technology growing across the next decade. Increasingly, states are already adopting water quality standards for the use of recycled water. Georgia has proven a leader, he adds.

And as water and sewer costs rise, the recycling facility offers a hedge on inflation. To construct the WaterHub, Sustainable Water shouldered all upfront costs to build and operate it. Emory has a purchase agreement to buy back recycled water. “Visitors can’t believe we were able to construct this state-of-the-art technology with no upfront costs to Emory,” Howett says.

As the facility reaches its fifth anniversary, Howett can’t help but look back to the WaterHub’s opening in April 2015. “It felt like Emory was planting a flag, proclaiming that we are going to be leaders, not followers, in this space,” she says.

“I think the WaterHub represents what is best about Emory,” Howett adds. “In a way, it is our commitment to ethical, courageous leadership made manifest in bricks, mortar, concrete and steel. That’s what makes me proud: When we say we want to be a place of innovation and discovery and we’re doing it.”

Written by Kimber Williams and Roger Slavens. WaterHub illustrations by Nate Padavick. Photography by Stephen Nowland. Design by Elizabeth Hautau Karp.