By Clare McCarthy, General Sustainability Intern, Office of Sustainability Initiatives

Throughout the majority of American history, environmental and racial issues have been perceived as existing in separate spheres. This understanding shifted irreversibly with the work of the United Church of Christ (UCC), a national church-based civil rights agency, and its Commission for Racial Justice. The Commission was a driving force in the birth of the environmental justice (EJ) movement by exposing the deeply rooted connection between race and environmental injustices. This connection is captured by the term “environmental racism,” coined by Dr. Benjamin Chavis during a protest against the siting of a hazardous waste disposal facility in Warren County, North Carolina. Chavis defines environmental racism as a broad issue that includes discriminatory practices like the unequal enforcement of environmental laws (Jeffreys 1994).

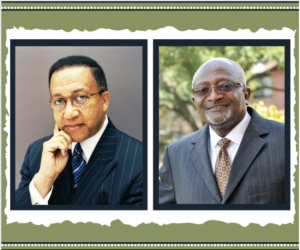

Dr. Chavis took the lead as the executive director of the UCC’s Commission for Racial Justice. In 1987, he commissioned the first national report to examine the relationship between race and the disposal of hazardous waste, “Toxic Wastes & Race in the United States.” Uncontrolled toxic waste raises numerous public health concerns. For instance, it can contaminate groundwater, which served as a source of water for 75% of American cities at the time of the report.

The report found that race was the most significant predictor of the location of commercial hazardous waste facilities. In other words, communities with the greatest number of hazardous waste facilities had the highest composition of racial minority residents. For instance, communities with two or more waste facilities, or one of the country’s five largest landfills, had a percentage of minority residents that was over three times the minority percentage of communities without such facilities.

These findings were especially pronounced for Black and Hispanic Americans– three out of every five Black and Hispanic Americans lived in communities with uncontrolled toxic waste sites. Furthermore, metropolitan areas with the greatest number of uncontrolled toxic waste sites had a disproportionate representation of Black residents in their population. Atlanta occupied sixth place on this list, with 94 toxic waste sites and a population consisting of 46.1% of Black residents (CRJ 1987).

Dr. Chavis intended for this data to galvanize governments at all levels to prioritize the cleanup of uncontrolled toxic waste sites in Black, Hispanic, and low-income communities. Due to his impressive work, he was invited to join the Clinton-Gore transition team as an advisor on environmental justice (EJ) matters (New York Times 1994).

Dr. Robert Bullard is another central figure in the EJ field and is known as “the father of environmental justice.” He built upon Chavis’s work by contributing to the “Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty” report, which marked the 20th anniversary of the first UCC report. Ultimately, Bullard’s report found that racial disparities in hazardous waste distribution are even greater than previously suspected. One particularly concerning example of environmental racism in the report is Dickson, Tennessee in the 1990s. There, a Black family suffered severe health issues after drinking well water that had been contaminated by a leaky landfill. Even after the government became aware of the issue, they did not take action for 12 years. On the other hand, White families in the town received swift responses to their contaminated water supply (CRJ 2007).

Dr. Bullard is currently the Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern University and an award-winning author of 18 books (Dr. Robert Bullard). Emory Climate Talks had the incredible honor of hosting Dr. Bullard last December. His presentation slides can be accessed here.

In the words of Dr. Bullard, eliminating racism and classism in addition to environmental degradation is necessary to “make sure communities are sustainable and livable.” His vision of communities where every individual has access to safe food, water, and green space is “achievable if we view it as important” (Milman 2018). Thanks to the efforts of Black leaders like Dr. Chavis and Dr. Bullard, more Americans are confronting the need to advocate for environmental justice issues, including clean water for all, with the urgency and importance which they require.

Citations

A Bridge Too Far?; Benjamin Chavis. (1994, June 12) New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/12/magazine/a-bridge-too-far-benjamin-chavis.html?pagewanted=3.

Biography: Dr. Robert Bullard, Father of Environmental Justice (n.d.). Dr. Robert Bullard. Retrieved from https://drrobertbullard.com/biography/.

Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ), United Church of Christ. (1987). Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. Retrieved from http://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/unitedchurchofchrist/legacy_url/13567/toxwrace87.pdf?1418439935.

Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ), United Church of Christ. (2007, March). Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: 1987-2007. Retrieved from https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/toxic-wastes-and-race-at-twenty-1987-2007.pdf.

Jeffreys, K. (1994). Environmental Racism: A Skeptic’s View. Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development, 9(2), Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.ecosia.org/&httpsredir=1&article=1484&context=jcred

Milman, O. (2018, December 20). Robert Bullard: ‘Environmental justice isn’t just slang, it’s real.’ The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/dec/20/robert-bullard-interview-environmental-justice-civil-rights-movement