by: Caroline McCormack, OSI General Intern

Rivers and creeks in Atlanta are fundamental to the health and well-being of our communities. They create opportunities for recreation and connection with nature, and they harbor hundreds of wildlife species. (1,2) Most of metro-Atlanta’s drinking water supply comes from the Chattahoochee Water Basin, which includes Lake Lanier and the Chattahoochee River. (3) Over the last several decades, one of the biggest threats to Atlanta waterways has been pollution from problem-prone sewage infrastructure. Remediating sewage pollution in Atlanta is an ongoing, decades-long struggle. While this is a success story for some communities that have seen major improvements in water quality, marginalized communities in west and south Atlanta are still burdened with disproportionate levels of sewage pollution. Addressing pollution through an environmental justice lens is imperative to protecting the well-being of everyone in Atlanta.

Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs) and Sanitary Sewer Overflows (SSOs) spill millions of gallons of sewage into Atlanta creeks and rivers every year. (4) In combined sewer systems, sewage, rainwater drainage, and industrial wastewater are collected into the same pipes and flow to a treatment plant. Combined Sewer Overflow events (CSOs) occur after heavy rainfall when the volume of water flowing through the pipes exceeds the wastewater treatment plant capacity. Some excess water must be diverted to nearby waterways, contaminating them with untreated or partially treated sewage. (3)

Unlike combined sewers, sanitary sewer systems separate sewage from other wastewater sources. Sanitary Sewer Overflow events (SSOs) occur when blockages, breaks, or heavy rainfall cause the system to overflow, spilling sewage into nearby creeks or out of manholes into city streets. (4)

SSOs and CSOs present a serious public health threat because pathogenic fecal bacteria is spilled into waterways where Atlanta residents swim, play, and source their drinking water. In a recent study, researchers at Emory Rollins School of Public Health investigated CSOs in Atlanta from 2002 to 2013. They found that CSOs were associated with a 9% increase in emergency room visits for gastrointestinal illnesses in the following week. (3)

Since many CSOs and SSOs occur after rainfall, they also share a connection to climate change. The southeastern United States has seen an increased number of rainy days over the last decade, (3) and it is expected to see more extreme precipitation as climate change progresses. (5) As such, fixing the sewage infrastructure to prevent future CSOs and SSOs will bolster the city’s climate resilience.

In 1994, a group of community members concerned about the overwhelming trash and sewage pollution in the Chattahoochee River formed the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, an organization dedicated to protecting and cleaning up the river. (1) As a brand-new organization, they sued the city of Atlanta in 1995 for non-compliance with National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. These permits impose limits on the amounts of bacteria and other pollutants in a facility’s wastewater discharge. (4) The lawsuit resulted in a consent decree requiring the city to fix its combined sewer system and fully comply with the NPDES permits and clean water laws. In 1998, another lawsuit resulted in an amendment to the consent decree that required the city to fix its sanitary sewer infrastructure and eliminate all SSOs. (4,6)

In 2008, Atlanta completed the construction and operational improvements to CSO facilities that were required in the consent decree, drastically reducing CSOs. Before 2002, Atlanta saw 50-70 CSOs per year, but fewer than 20 unpermitted CSOs have occurred since the city finished construction. (4,6,7) By 2012, Atlanta had reduced the volume of SSOs by 95% compared to 2004. In the same year, the city received an extension, pushing the deadline for completing the remaining construction to 2027. (4)

While these improvements made a difference in water quality throughout the city, they do not tell the full story. Past and present issues with the sewer system have primarily impacted black and low-income communities in south and west Atlanta, leaving them swamped with pollution and contributing to disparities in health and quality of life.

In 1992, nearly 80% of CSOs occurred in majority African-American and low-income areas. (8) In west Atlanta, concerns about the stench and safety risk from raw sewage spills in a local public park led residents near Utoy Creek to organize. In the early 1990s, they formed the Environmental Trust to advocate for the concerns of communities who were left out of sewage infrastructure planning. Their lobbying prevented the construction of a new CSO facility on Utoy Creek and led to the separation of sewage pipes from stormwater runoff in the area near Utoy Creek and part of Proctor Creek, eliminating CSOs in that area. (8)

The West Atlanta Watershed Alliance (WAWA) grew out of the Environmental Trust to address the slew of unjust environmental hazards impacting in the Utoy Creek and Proctor Creek watersheds. In addition to sewage pollution, this primarily black and working-class community faces illegal dumping, erosion, air pollution, industrial pollution, and toxic waste sites. (9) WAWA’s programs include a partnership with the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper to monitor water quality in West Atlanta streams. Years after the combined sewer system was separated, this program identified ongoing E. coli contamination in Proctor Creek. This led the city to identify and fix dozens of pipes they had missed when the system was initially separated. (9,10,11)

Spillage of raw sewage through unpermitted CSOs is now rare, but Atlanta CSO facilities discharge treated sewage into creeks dozens of times per year. (7) This is legal as long as the sewage discharge meets NPDES permit requirements. However, that does not mean the sewage discharge is harmless to local ecosystems and communities. Sediment, ammonia, phosphorus, and metals, which are not closely monitored, can harm fish and aquatic life. (6)

Moreover, the majority of sewage discharges today occur only in certain areas. Most unpermitted CSOs (unintentional spills of untreated sewage) in the last decade occurred from only two facilities: the West Area Water Quality Control Facility (WQCF), that discharges into Peachtree Creek just upstream from the Chattahoochee River, and the Intrenchment Creek Pollution Control Facility at Key Road immediately upstream from the South River.

Most permitted discharges (intentional spills of treated sewage) occurred from the West Area Water Quality Control Facility and the Custer Avenue CSO facility, which also discharges into Intrenchment Creek near the Atlanta Federal Prison. (7)

Intrenchment Creek is a tributary of the South River, which flows through a primarily black and low-income community with a long environmental justice history. (12,13) This river receives much of the pollution from both unpermitted and permitted discharges, which places a disproportionate environmental burden on the surrounding community. (12) The South River is designated for “fishing” use, which is Georgia’s lowest designation with the least stringent water quality standards. Due to a lack of enforcement from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GA EPD), the South River has never even achieved this level of water quality. (4,14)

The South River Watershed Alliance hosts guided paddles to build community support for the South River and encourage more people to use it recreationally. The organization’s goal is to push GA EPD to change the South River use designation to “recreation.” This small action would raise water quality standards, and with proper enforcement, drastically reduce pollution. (15) In 2021, the designated use of a 13-mile section of the river was changed to recreation.

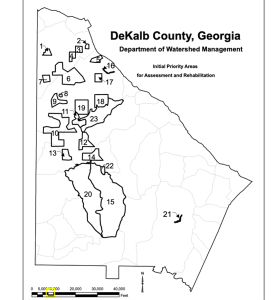

The city of Atlanta is not the only local government responsible for the deluge of sewage polluting the South River. In 2010, more than five decades of sewage pollution led the EPA to investigate the Dekalb County sewage system. This resulted in a consent decree requiring the county to eliminate all SSOs, with a deadline to fix the sewage infrastructure in “priority areas” by 2020. (6) A 2021 amendment expanded the priority areas, but it did not provide a deadline for improvements to the rest of the sewer system. (16)

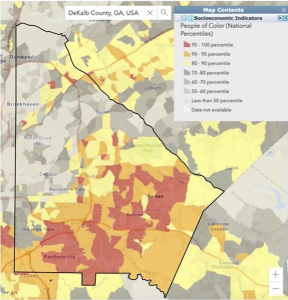

The priority areas encompass parts of northern and western Dekalb County, but they include less than a third of the county’s sewer system. Most sewer spills happen outside of the priority area, and the county has no deadline to make improvements to the other two-thirds of the system. South Dekalb County, where a majority of residents are people of color, is mostly left out of priority areas. (6,17) Yet all Dekalb residents are paying higher water and sewer bills to fund improvements that mostly benefit white and wealthier communities in north Dekalb. (18) The South River Watershed Alliance is fighting this environmental injustice by petitioning the EPA to amend the consent decree by removing the “priority” language and imposing deadlines requiring Dekalb County to comply with clean water laws in the entire county. (https://www.southriverga.org/advocacy)

In large part due to advocacy and whistleblowing from community members, drastic improvements have been made in the Atlanta sewage system since the 1990s. However, discriminatory policies and unequal enforcement have left behind black and low-income communities in west and south Atlanta, over-burdening them with sewage pollution. Organizations like WAWA and the South River Watershed Alliance are fighting to address environmental injustice in these communities because everyone in the Atlanta area deserves equal access to clean, safe water and recreation in nature.

Top: Demographic Indicators: People of Color. EPA EJ Screen. Outline of Dekalb County added for clarity. Bottom: Northern District Court of Georgia, Atlanta Division. The United States of America snd the State of Georgia v. Dekalb County, Georgia: Consent Decree. Civil Action No. 1:10-cv-04039-WSG. U.S. Environemntal Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/documents/dekalb-cd.pdf

Acknowledgements

Dr. Jaqueline Echols, South River Watershed Alliance, Board President

Dr. Na’Taki Osborne Jelks, West Atlanta Watershed Alliance, Co-Founder and Board Chairperson

Nicholas Chang, 24C

References

- “Chattahoochee Riverkeeper Celebrates 25 Years of Stewardship from the Mountains to the Sea.” Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, 2019, https://chattahoochee.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CRK_25_YEAR_REPORT_DIGITAL_FINAL.pdf.

- “Animals.” Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, National Parks Service, https://www.nps.gov/chat/learn/nature/animals.htm.

- Miller, Alyssa G., Ebelt, Stephanie, Levy, Karen. “Combined Sewer Overflows and Gastrointestinal Illness in Atlanta, 2002-2013: Evaluating the Impact of Infrastructure Improvements.” Environmental Health Perspectives, 130, no. 5, 2022, pp. 57009, https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/EHP10399.

- Butler, Kathlene; Hamann, Julie; Roach, Tim; Ross, Johnny. Atlanta is Largely In Compliance With Its Combined Sewer Overflow Consent Decree, but Has Not Yet Met All Requirements. Report No. 18-P-0206, U.S Environmental Protection Agency, 2018, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-05/documents/_epaoig_20180530-18-p-0206.pdf.

- Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Comis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., editors. “IPCC 2021: Regional Fact Sheet – North and Central America.” Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, 2021, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/factsheets/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Regional_Fact_Sheet_North_and_Central_America.pdf.

- Echols, Jaqueline. “Environmental Justice in Clean Water Act Implementation – National 303(d)/TMDL Webinar Series.” Youtube, uploaded by NEIWPCC, March 30, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S1zSHNU-e0Q&t=1600s.

- CSO Consent Decree Quarterly Status Reports, 2012-2022. Department of Watershed Management, City of Atlanta, 2022. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/16Q-CJLAeVRg6h2LHtM9q6jR0Gh31P-FR

- Osborne Jelks, Na’Taki. “Sewage in Our Backyards: The Politics of Race, Class + Water in Atlanta, Georgia.” Projections Volume 8: Justice, Equity, + Sustainability, MIT Journal of Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2022, http://web.mit.edu/dusp/dusp_extension_unsec/projections/issue_8/issue_8_jelks.pdf.

- “Advocacy Work.” West Atlanta Watershed Alliance, https://www.wawa-online.org/ugro-garden.

- “History.’ West Atlanta Watershed Alliance, https://www.wawa-online.org/history.

- “Proctor Creek Still Plagued by Problems, despite Millions in Fixes.” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 23 Jan. 2014, https://www.ajc.com/news/proctor-creek-still-plagued-problems-despite-millions-fixes/VuK77AMc8XqXAM9k9KefWP/.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2022 version, https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/. Accessed 9 July, 2022.

- “What is the South River Forest?” South River Forest Consensus Building & Stakeholder Engagement, https://publicinput.com/SouthRiverForest#2.

- “Challenges.” South River Watershed Alliance, https://www.southriverga.org/challenges.

- “Recreation.” South River Watershed Alliance, https://www.southriverga.org/recreation.

- Northern District Court of Georgia, Atlanta Division. The United States of America snd the State of Georgia v. Dekalb County, Georgia: Modification to Consent Decree. Civil Action No. 1:10-cv-04039-SDG, Dekalb County, https://www.dekalbcountyga.gov/watershed-management/consent-decree-cd. PDF download.

- “A Dangerous Precedent is Threatening the Clean Water Act!” South River Watershed Alliance, https://drive.google.com/file/d/17ntUaYb5bKXaQSGhfZifRVu7CACfP7pr/view.

- Echols, Jaqueline. June 23, 2022. “Letter to Daniel Blackman, EPA Administrator, Region 4.” Provided through personal communication with Dr. Echols. Accessed July 14, 2022.

I really enjoyed reading this blog post on environmental justice and sewage pollution in Atlanta. It’s fascinating to learn about the intersections between social inequalities and environmental issues, and this article did a great job of highlighting that. I appreciated the discussion of how certain communities bear the brunt of pollution and how we need to work towards solutions that address these disparities. It’s a reminder that sustainability is not just about protecting the environment, but also about ensuring that everyone has access to a healthy and livable community.

The issue of sewage pollution in Atlanta and its impact on environmental justice is a critical one that requires urgent attention. It is unacceptable that communities, especially those with a high proportion of low-income residents and people of color, continue to bear the brunt of environmental pollution and its associated health risks. It is commendable that Emory University is partnering with organizations like the West Atlanta Watershed Alliance and the Peoplestown Revitalization Corporation to address this issue.

In addition to these efforts, there is a need for comprehensive action to prevent sewage pollution in the first place. This includes investing in infrastructure upgrades and maintenance, increasing public awareness of the importance of proper waste disposal, and enforcing laws and regulations to hold polluters accountable. We must prioritize the health and well-being of our communities and work towards a more sustainable and equitable future.